From Patients to Prisoners: A Modern History of Mt. McGregor - Part Two

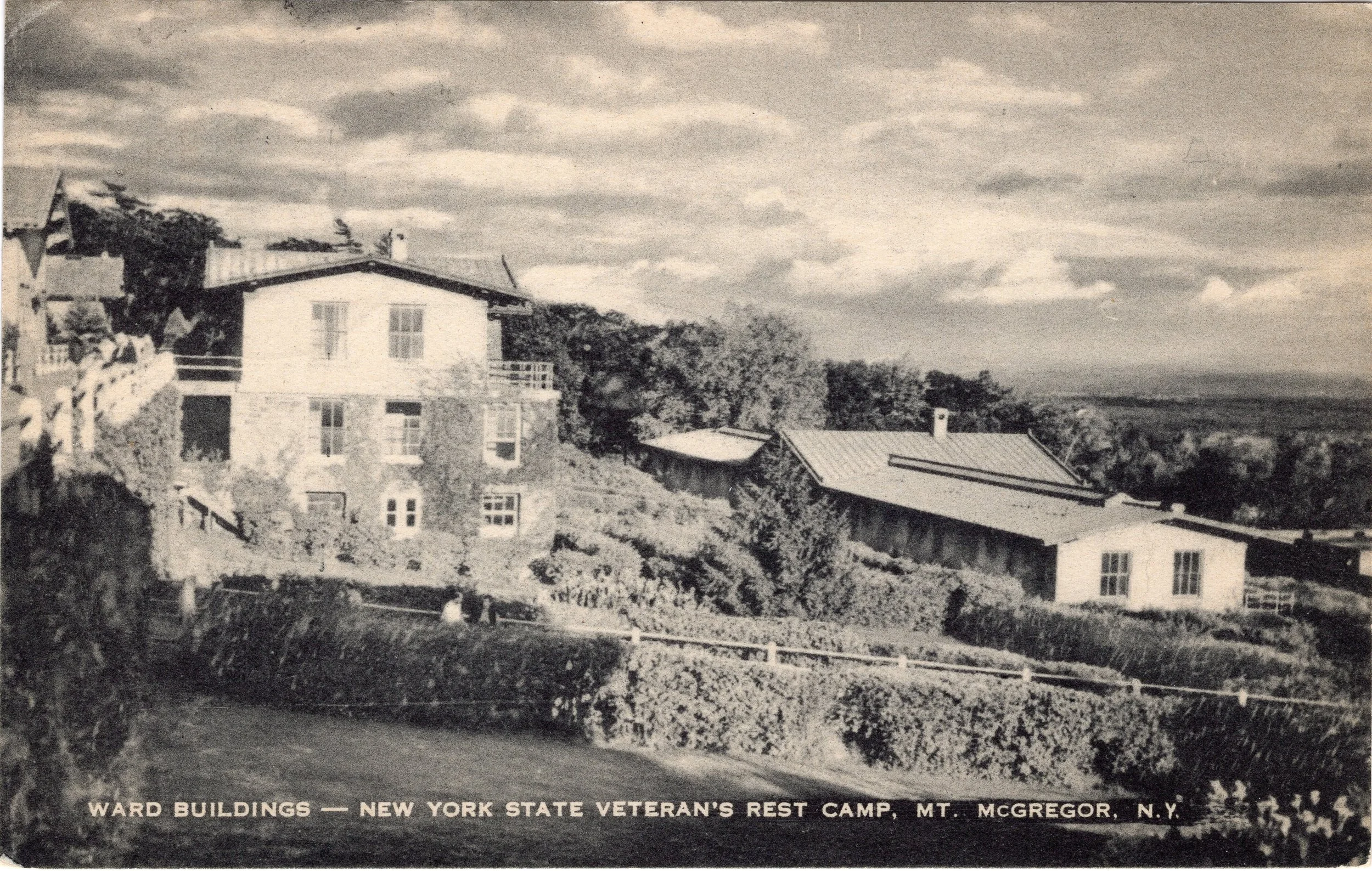

Postcard image of the New York State Veterans Rest Camp at Mt. McGregor.

WW II soldiers returning to New York City. Source: Library of Congress

From The Binghamton Press 8/22/1945

From War Department pamphlet “Going Back to Civilian Life” (1945)

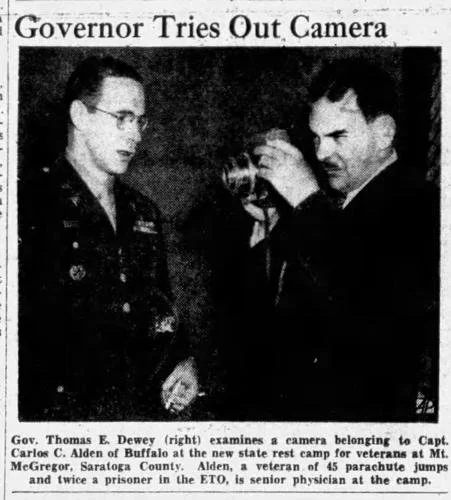

As World War II was coming to a close the attention of the Veterans Administration shifted toward the massive influx of returning soldiers (1.5 million served from New York State). A major priority was preparing the veterans for the transition to civilian life, which was a major component of the famous “GI Bill” passed in 1944. Soon after MetLife announced the plan to close its Mt. McGregor sanatorium in June 1945, the use of the facility for veterans was proposed. In August 1945, New York Governor Thomas Dewey visited Mt. McGregor and announced that New York State would indeed be purchasing the facility for use as a veterans’ camp.

From The Post Star 11/14/1945

It was a rapid transition as the MetLife sanatorium closed officially on Sept. 1 and Gov. Dewey officially opened the New York State Veterans Rest Camp on Mt. McGregor on Veterans Day (Nov. 11) in front of the 35 veterans newly admitted there (first patients on Nov. 1). Dewey stated that the facility was “the first concrete expression of the attitude and gratitude of the people of the State of New York for the men who fought so gallantly to preserve our liberty.” The governor toured the facilities and even took part in some recreational fun in the form of table tennis and bowling. The camp was available to New York State veterans (men or women) and veterans living in the state for a year or more. Interested veterans could request a stay of up to 90 days with a note from a physician.

From The Post Star 11/14/1945

The purpose of the facility was not as a long-term medical care facility, despite the requirement of a physician’s note to apply, but rather a place for recovery and re-adjustment. It was also for “discharged veterans not eligible for Federal hospital care or veterans discharged from Federal hospitals who are still in a convalescent stage.”

“War-weary New York State veterans who find the rigors of civilian life not to their liking may now get away from it all for up to ninety days.” - Middletown Times Herald 4/22/1946

The camp was open to New York veterans from all conflicts, but preference was given to those who most recently returned from service in World War II. Counselors were appointed in each county of New York State to assist local veterans, and they put out frequent notices in the newspapers to inform veterans of the opportunity to attend the Mt. McGregor camp. Transportation to and from the camp could be provided.

Maj. Tegtmeyer (left) being appointed superintendent of Mt. McGregor camp by Edward J. Neary (center) of the Department of Veteran Affairs and Gov. Dewey (right). From: The Times Union 10/9/1945

While the veterans’ experience at the rest camp included leisure and recreation time, the vets were also encouraged to take part in vocational tasks and training, such as farm or maintenance work. The first Superintendent of the Rest Camp, Dr. Charles E. Tegtmeyer, a decorated World War II combat surgeon, said that the camp would not become a home for the “lazy” or “professional loafers.” No firearms, private alcohol, or gambling were permitted.

The daily schedule of a veteran at the camp was described in 1945:

“The veteran’s day begins at 7:15. Breakfast at 8 is cafeteria style, as are all meals except on special occasions, when nurses are employed to serve. From 9 to noon, veterans have a work period, and at 12:30, dinner is served. The afternoon is devoted to recreation and occupational therapy. After supper, veterans may attend the theater, social hall, or recreational hall until 10:00. Comes 10:30 - lights out.”

The dining hall at the Veterans Rest Camp on Mt. McGregor

The Rest Camp was supplied by farms in the nearby valley, just as the sanitorium before it. In 1945, the state allowed 80 cents per day per veteran for food provisions. The food was served in the spacious dining hall featuring tall windows overlooking the Hudson River Valley. The food was described as “excellent.” Those confined to bed were served their meals by the nursing staff.

Veteran served dinner in bed. From: The Saratogian 11/12/1957

The dining hall at the Rest Camp.

Chow time: patients line up at the camp’s cafeteria for spagetti dinner. From: The Saratogian 11/12/1957

The Camp Library at Mt. McGregor. From: The Saratogian 11/12/1957

The administration building.

Sign for Mt. McGregor Veterans’ Camp. From: The Saratogian 11/12/1957

Veterans upon admission were given a medical evaluation to determine the appropriate level of activity for them to engage in. They were assigned to activity groups 1-highest through 5-lowest. For their recreational time, camp veterans had many opportunities to choose from:

Veterans playing billiards in 1955. From: The Daily Gazette

“Two bowling alleys, pool, and ping-pong tables are available, together with a 3,000-volume library. Recreation buses are run to Saratoga Springs and Glens Falls. Skiing and skating are winter sports, and plans are underway to convert Artist Lake into a swimming pool with bathhouses and modern bathing facilities. Tennis courts, a croquet lawn, and a baseball diamond also are on the recreation list.”

Veteran making poppies. From: The Saratogian 11/12/1957

The veterans took part in competitive sports such as bocce, shuffleboard, volleyball, badminton, tennis, and archery, with the Mt. McGregor veterans softball team regularly playing other local clubs. Films and other live entertainment, like magicians, comedians, music, and theatrical productions, were available at the auditorium multiple times a week.

Occupational therapy opportunities included leathercraft, metal work, ceramics, bookbinding, photography, art, and woodworking. Making Buddy Poppies for the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) to sell. woodworking,

In 1948, it was estimated that 100,000 veterans in New York were in need of educational and vocational opportunities, and 6000 were in medical facilities. Not only did the camp provide a place of rest and camaraderie with fellow veterans, but it could help faltering vets get stabilized and improve their opportunities.

“Old soldiers don’t die here, they recuperate. ”

The auditorium building at the Rest Camp.

Artists Lake in the center of the camp offered fishing and swimming for veterans.

12 foot high ice sculpture “King Winter” created by Donald Favreau and two other veterans. From: The Times Record (Troy, NY) 3/6/1947

Winter could be a more challenging season on the mountain, but the veterans made the best of it. World War II veteran Donald Favreau was the athletic and recreation director for the camp in 1947. As a former 10th Mountain Division Ski Trooper while in the military, he taught thousands of vets how to ski at the camp. Skating on Artist Lake was also a popular activity, snowshoeing, tobogganing, and even ice sculpting.

Donald Favreau training in 1943.

Veterans needed to secure permission to leave the camp, and there was a security station down the road from the camp to check passes. Sometimes, the veterans went on organized excursions offsite, such as the Sandy Hill Iron and Brass Works company field day and picnic at Summit Lake in nearby Washington County in the summer of 1946.

An overlook of the Hudson River a couple of miles hike from the camp.

Veterans on the grounds of the camp in 1955. From: The Daily Gazette

The veterans who came to Mt. McGregor came from all over the state and served in many different capacities while in the military. There was Corporal John P. Carp, who was wounded and captured in the Battle of the Rhineland offensive in 1944, and spent six months in a German prisoner of war camp. Carp had three brothers and a brother-in-law who also served, one of whom died in combat. Some were from earlier wars, like 72-year-old Charles C. Munson, who served in the fledgling Air Service in World War I. Mrs. Maude H. Bryson had served as a nurse in World War I in France and came to Mt. McGregor. Bryson, who was 5 years old when Civil War veteran Ulysses Grant died on Mt. McGregor in 1885, stayed in the women’s cottage with the other resident ladies. She found the views inspiring and a sense of community while at the camp.

From: The Times Union 12/23/1959

From: The Times Union 12/23/1959

Occasionally, couples like Harry M. Messinger, a World War I veteran who had marched in the “Welcome Home Parade” on 5th Avenue in 1919, and his wife, Beatrice, who had served with the Women’s Army Corps in World War II, stayed at the camp together. They reported that it was “like a country club,” and the vets received “the finest treatment possible. World War II veteran and Purple Heart recipient Anthony “Tony” Gambino found much more than most on Mt. McGregor. Gambino married the resident caretaker of Grant Cottage, Suye Narita, in the summer of 1950 and would be associated with the mountain for the rest of his life. The Korean War of the early 1950s brought a fresh wave of veterans to the camp. The ages of the veterans spanned two centuries, with 20-year-old Korean War vet Curtis Gregory sharing the camp with 81-year-old Spanish American War vet Phillip Basson in 1952.

World War I veteran Charles C. Munson at the Rest Camp in 1957. From: The Saratogian 11/12/1957

John “Jackie” Donovan at the Rest Camp. Courtesy of the Wilton Town Historians Office.

The chapel at Mt. McGregor.

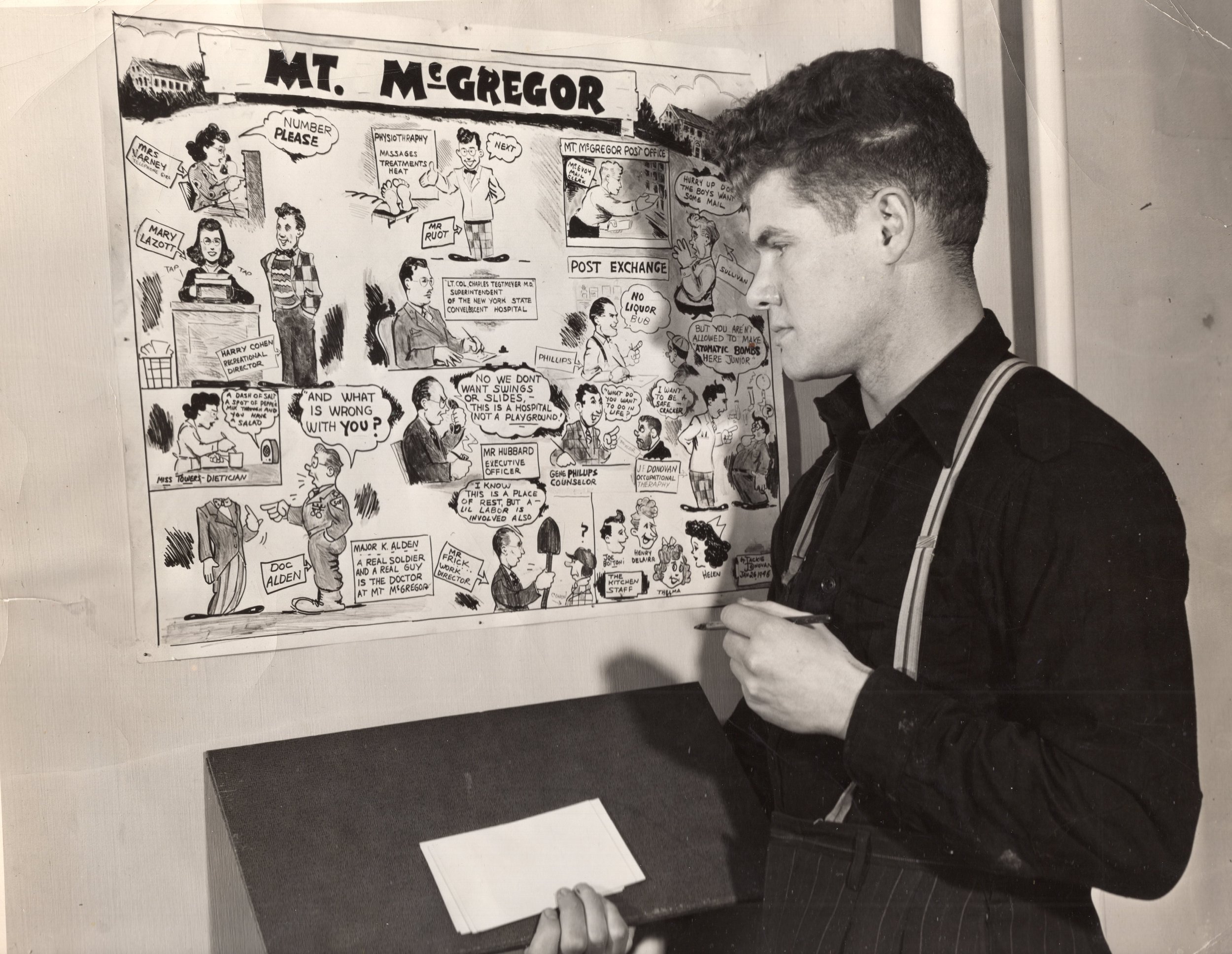

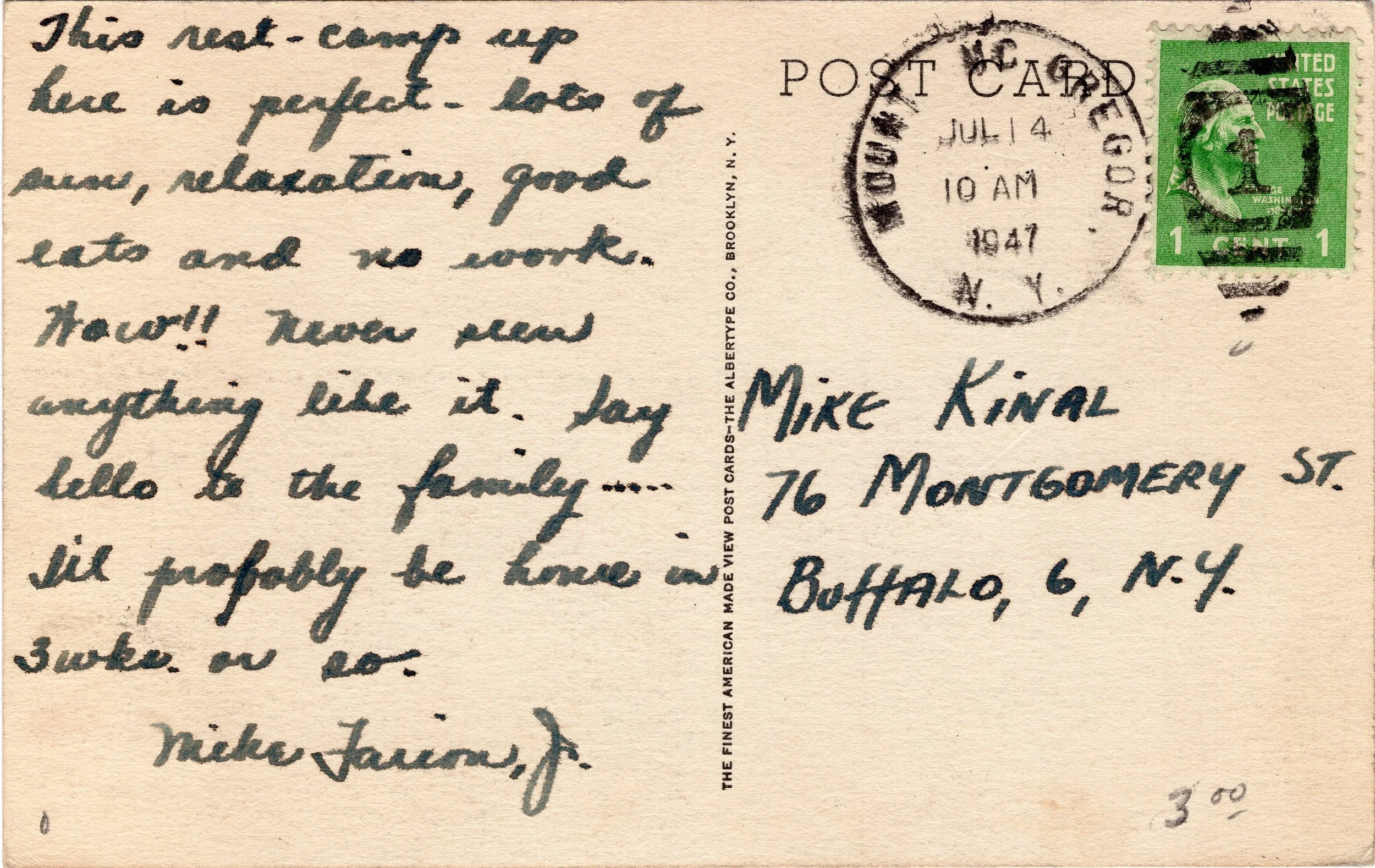

Just like the sanitorium before it, the Rest Camp published a weekly newsletter, and it was called “Mountain News.” One regular contributor was World War II veteran John “Jackie” Donovan, a cartoonist and professional boxer. Other holdovers from the sanitorium days were the chapel, where the vets and staff could worship according to their particular faith, and the official Mt. McGregor Post Office, where veterans like Michael Farion Jr. sent postcards to friends and family, updating them on their experiences and health while at the camp.

Mt. McGregor Post Office. From: The Saratogian 11/12/1957

Post card sent by Michael Farion Jr. from Mt. McGregor to Pearl Harbor survivor Michael Kinal in 1947.

“The rest camp up here is perfect - lots of sun, relaxation, good eats and no work. Wow!! Never seen anything like it. ”

A northeast view from the camp.

Raising the flag at the Eastern Overlook on Mt. McGregor in May 1952.

The significance of the mountain’s most famous resident was not lost on the veterans who came there. Memorial services were held at the Grant Cottage historic site annually, with camp veterans attending. In May 1949, a special guest came to the mountain. Major General Ulysses Grant III came and visited the cottage where he had stayed when his famous grandfather died over 60 years before. Ulysses III graduated from West Point Military Academy and had a distinguished career through both World Wars. The last Civil War veteran known to visit the cottage was Leroy Barnard, who spoke there in 1942 at the age of 99. The Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War had taken over observances at Mt. McGregor by the 1940s-50s.

The camp celebrated a significant milestone in 1958 when Edward J. McLaughlin, head of the New York Division of Veterans Affairs, presented a certificate to World War I naval veteran Augustine McCullough as the 30,000th admission to the camp. This meant the camp had provided care for an average of over 2500 veterans a year. About twice as many veterans —up to 600 at a time —could be accommodated in the warmer months, as opposed to the winter months, due to heating limitations.

Camp Director George Hubbard greeting new admissions to the camp in 1955. From: The Daily Gazette

George Hubbard. From: The Saratogian 11/12/1957

One individual who was a mainstay at Mt. McGregor over the years was World War I veteran George E. Hubbard. Hubbard had started work for the sanitorium in 1921 and transitioned to become business manager at the Rest Camp and eventually director. Hubbard would continue on the next phase of the facility’s history as well, finally retiring in 1963 after over 40 years on the mountain.

By the late 1950s, the camp became a bit of a political football. There were accusations of the camp being a “lavish” place for “plush free vacations” for the vets. Plans to close the facility were met with stiff resistance by veterans’ advocacy groups, including the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). The resistance succeeded in keeping the camp open for a time. In the spring of 1959, the veterans held a Memorial Day program at the camp. Decorated World War II naval veteran William L. Ford of nearby Saratoga Springs was the main speaker. Ford expressed a desire to see the facility continue to serve veterans perpetually. 150 veterans marched to the towering flagpole in front of the camp with the color guard to raise the colors. Wreaths were laid to commemorate servicemembers from both World Wars, the chapel bells tolled, and Taps was played. Applications stopped being accepted in April 1960, and the end finally came in September, when New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller officially closed the camp. The last veterans left, and the next chapter of the mountain’s history was about to be written.

The flagpole on the front of the camp.

Veteran with a missing leg at the camp.

There may not be any veterans walking the grounds of the camp anymore, and most who once did have since passed on, but just as their most famous fellow veteran, Ulysses S. Grant, their memories linger on. As Grant once said:

““Let their heroism and sacrifices be ever green in our memory. Let not the results of their sacrifices be destroyed. The Union and the free institutions for which they fell, should be held more dear for their sacrifices.” ”

Grant Cottage Historic Site is proud to welcome veterans to Mt. McGregor, hosting about 750 annually to enjoy the peacefulness, inspiring views, and rich history just as their fellow servicemembers did in the middle of the last century.

Fall sunrise at the Eastern Overlook flagpole.

Sources:

The Massena Observer, 10/11/1945

Ogdensburg Journal, 8/6/1946

The Glens Falls Post Star, 11/3/1945, 7/22/1946

The Glens Falls Times, 8/2/1952

The Ballston Journal, 6/14/1945

The Saratogian, 9/29/1945, 5/26/1947, 6/2/1959, 8/16/1966

The Danville News 11/12/1945

Hammond Advertiser, 7/4/1946

The Daily Sentinel (Rome, NY) 6/10/1947

The Times Record (Troy, NY) 5/4/1942, 6/3/1946

The Times Union, 10/9/1945

The Brooklyn Eagle, 2/28/1947

The Tupper Lake Free Press and Tupper Lake Herald, 3/4/1948

The Ogdensburg Advance-News, 4/20/1958

The Evening Recorder (Amsterdam, NY), 7/1/1959

The Post Star, 2/27/1952